Depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and affects an estimated 17 million people each year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), by 2020, depression is projected to become the leading cause of disability and the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease (Murray & Lopez, 1996; WHO, 1996). Adding to the public health concern about depression is the projected increase in the aging population. By 2020, depression will be the second most common disease afflicting the elderly (Chapman & Perry, 2008).

Historical dehumanization, oppression, and violence against Black and African American people has evolved into present day racism – structural, institutional, and individual – and cultivates a uniquely mistrustful and less affluent community experience, characterized by a myriad of disparities including inadequate access to and delivery of care in the health system. Processing and dealing with layers of individual trauma on top of new mass traumas from COVID-19 (uncertainty, isolation, grief from financial or human losses), police brutality and its fetishization in news media, and divisive political rhetoric adds compounding layers of complexity for individuals to responsibly manage. (mhanational.org)

When it comes to dealing with depression, many Black men have not been told how to process and talk about their emotional experiences, furthering a sense of isolation, anger, and resentment. Many struggle with the idea of being openly vulnerable and sharing their emotions. And for those who grew up as sensitive boys, they are often subject to ridicule and shaming for what are natural and healthy expressions of emotion.

There have been unrealistic expectations based on gender and race that often keep many Black men and other men of color out of therapy. The stereotype is that men don’t like having to even seek advice so imagine the difficulty in saying to another person out loud, “I need some help.”

The very idea arising that something may be mentally wrong on the inside for the black male leads to a feeling of vulnerablity, therefore many will reject that a problem exists despite the daily struggle.

Over the years there is and always has been a great distrust towards medical providers by Black communities, especially among African American men. Think back to the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, wherein African American men were left untreated to study the progression of the disease. With that knowledge, it can be very easily understood why most black men very seldom take trips to see doctors or consider therapy.

So how can we change this narrative?

How do we encourage our black brothers that it is okay to not be okay?

Share your thoughts with us below on what changes you feel can take place to help our black men seek help when it comes to depression.

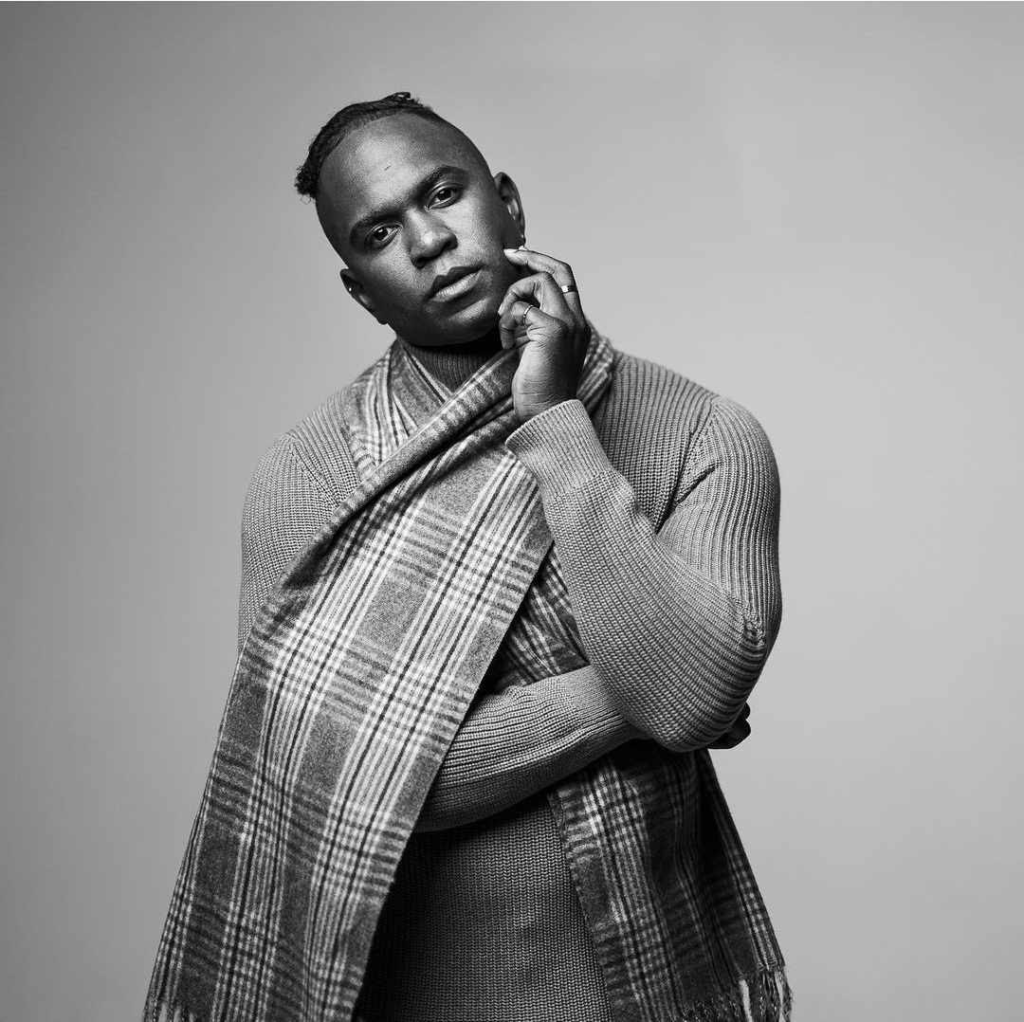

Photo by Amusan

Follow Us On Social Media!