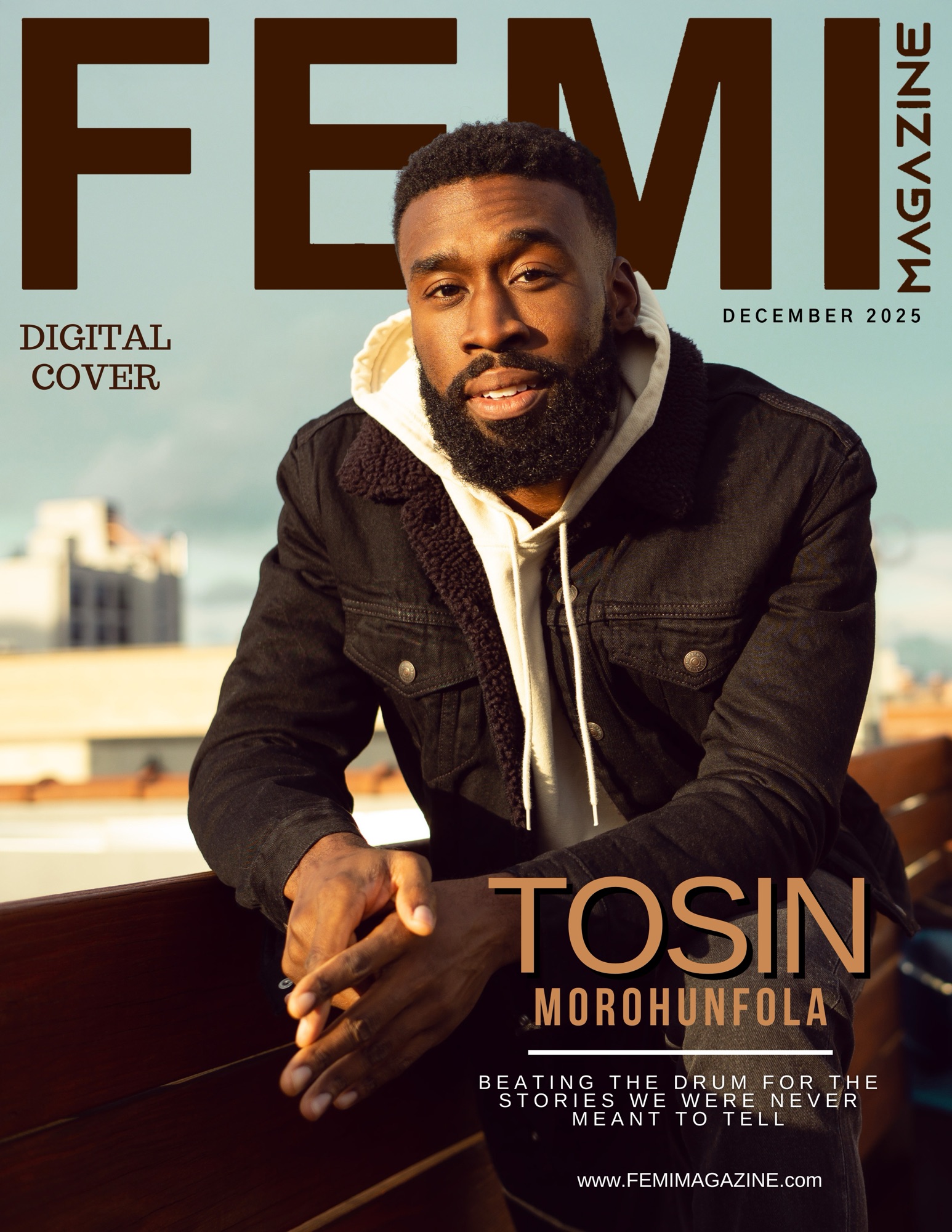

Actor, producer, director, and writer Tosin Morohunfola is stepping into one of his most vulnerable creative moments yet. For FEMI Magazine, Morohunfola opens up about The Drum Closet, a deeply personal new stage production inspired by his upbringing as a Nigerian-American kid in Kansas City, Missouri.

Set to run at The Coterie Theater from January 28 through February 22, 2026, the play is a coming-of-age story centered on two drum-obsessed African American brothers navigating a predominantly white Midwestern high school.

Timi is a wide-eyed freshman. Kareem is a senior standing on the edge of adulthood. Together, they face bias, bullying, rigid social hierarchies, and the unspoken rules that govern survival in white-majority spaces, all while competing for drumline section leader and striving to make their immigrant mother proud. Funny, rhythmic, urgent, and emotionally resonant, The Drum Closet explores what it means to grow up young, Black, talented, and vulnerable in a world that refuses to see you clearly.

The project arrives during a powerful creative run for Morohunfola. He recently appeared on STARZ’s Run the World, delivered a heartfelt performance in Tyler Perry’s Amazon film Finding Joy, and continues to build a career defined by intention. Rather than waiting for opportunity, he creates it, crafting the worlds he once searched for on screen and stage.

In this conversation, Morohunfola reflects on identity, masculinity, music, survival, and the personal legacy beating at the heart of The Drum Closet.

The Drum Closet is rooted in your own experience growing up as a Nigerian-American kid in Kansas City. What part of your real-life story felt most urgent to bring to the stage right now?

To be fair, it was a mix of the urgent and the timeless. We live in a country where the predominant narrative is always white-centered, and we live in a time where Black people’s stories are actively being erased. Nothing feels more pressing than bringing one of those stories to the forefront. Black kids growing up in the Midwest deserve to see themselves represented in a way they have been craving.

When Black bodies are so often ignored, or worse, endangered in white-majority spaces, giving voice to that experience feels essential. At the same time, this is a universal story about growing up and the trials of adolescence. That part is timeless. Everyone can relate to that journey.

The play follows two drum-obsessed brothers trying to survive a predominantly white Midwestern high school. What made you want to explore race, bias, and belonging through their eyes?

I saw it firsthand, both the good and the bad. I was raised in the suburbs of Kansas City, and I lived the life these protagonists depict. People are often surprised to learn how many Black people live there, and even more surprised to discover how many Africans are there.

I wanted to show what it is like being a Black kid in that environment, struggling with identity, competing to be the best, and balancing immigrant parents with high expectations. Unlike safer family plays, I wanted to explore uncomfortable realities like systemic racism, religious prejudice, policing, and patriarchy. But I also wanted to show triumph and how the bond of family can overcome so much.

This production blends Nigerian heritage, Midwestern culture, and Black musical tradition. How did you weave those influences together authentically?

It started with the drums. At home, we were raised on the percussive Afrobeats of Nigerian artists like Fela Kuti. At school, my brother Bunmi and I became obsessed with marching band and drumline. Drawing from both Afrobeats and marching drumming, I realized how metaphorical they were for my upbringing.

“Afrobeats represented culture, individuality, and heritage. Marching drumming, by its nature, is about assimilation, uniformity, and restrictive movement. It mirrored the pressure the white world places on Black children, from how we speak to how we behave. Blending these sounds allowed the music to demonstrate the pull a Black boy feels between two worlds.”

What do you hope audiences, especially young Black viewers, walk away with after seeing the play?

For Black viewers, I hope it connects us to our diasporic family and reminds us to honor where we came from. We are all some form of immigrant, and our past follows us whether we acknowledge it or not. The play shows how one person’s shame can become another person’s pride and how legacy pushes us forward.

For everyone else, while it touches on bullying, competition, and adolescence, at its core it is about identity and being true to yourself. Each character carries their own hidden fears and desires, stepping in and out of their own closets. Ultimately, the play reminds us that everyone deserves to explore their identity on their own terms.

You are an actor, producer, director, and writer who creates your own opportunities. How has that shaped your sense of purpose?

It is my compass. I feel a deep responsibility and social consciousness in everything I create independently. My mission is to shed light on dark places and empower the disempowered. Hollywood can be brutally commerce-driven, so creating my own work keeps me sane and grounded in my purpose.

There is nothing more empowering than taking your artistry into your own hands. When an artist is that committed, I think the industry eventually takes notice. I feel like that has been happening for me over the last decade.

How did your recent screen work influence how you approached this deeply personal project?

On Run the World, I played a character very similar to myself, a first-generation Nigerian American. It reminded me that my own life experience is valid and worthy of being told. I did not need to fictionalize.

On Finding Joy, I had the opportunity to contribute to rewrites, which strengthened my confidence in my voice and my pen. That process empowered me to trust myself more as a writer and storyteller.

Why was drumline culture the right metaphor for masculinity, code-switching, and surviving whiteness?

Drumline is seductive. The synchronicity, the groove, the adrenaline, it is intoxicating. But that culture can easily slip into something cult-like. In predominantly white marching bands, you learn to code-switch and survive by expressing your Blackness less.

Drumming is also male-dominated, which adds another layer when women or non-conforming men step into that space. The politics are real, and for a young Black kid, one misstep can feel life-altering. Drumline became the perfect metaphor for who I was at home versus who I was asked to be at school.

When you think about your younger self in Kansas City, what do you think he would say now?

I hope he would be proud. But honestly, I would be talking to my older brother Femi. He influenced me deeply and shaped my love for acting. Even now, I still seek his approval.

I believe he would be cheering me on, still guiding that compass inside me. And I do not think it is a coincidence that this interview is for FEMI Magazine. It feels like a reminder that he is still listening to my drums.

With The Drum Closet, Tosin Morohunfola is not just telling a story. He is reclaiming space, memory, and rhythm for a generation of young Black kids who learned early how to survive without ever being fully seen. Rooted in love, loss, music, and truth, the play stands as both a personal offering and a collective mirror, honoring the resilience it takes to grow up talented and vulnerable in a world that demands you shrink. As the drums echo across the stage, Morohunfola reminds us that sometimes the most powerful act of self-definition is choosing to be heard anyway.

Photography By: DANIEL WELCH

Follow Us On Social Media!