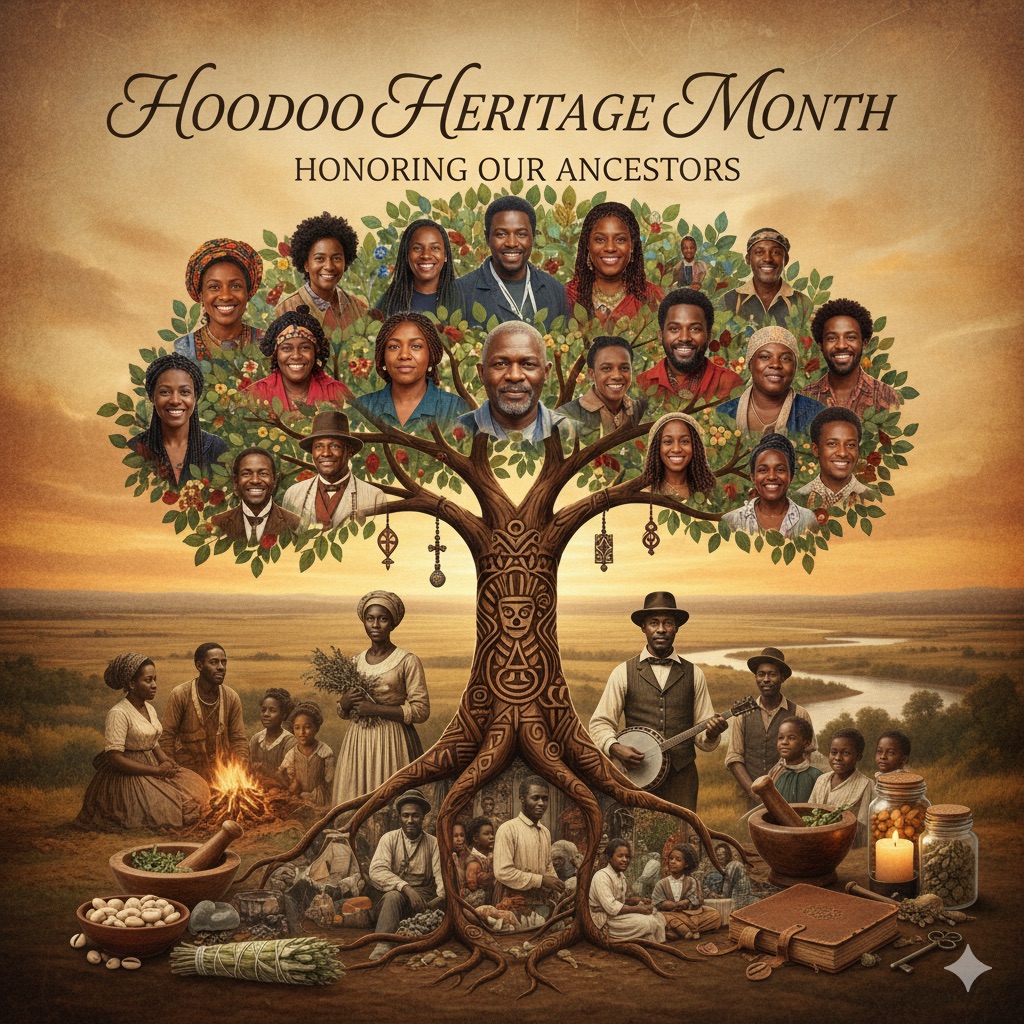

Hoodoo Heritage Month lives in October — yes, that month with the pumpkin spice and the people who suddenly remember cemeteries exist. The month was set aside to honor the lineage, history, and practitioners of Hoodoo — the conjure, rootwork, and herbal traditions created and sustained by African American communities — and to remind folks that this is a living culture, not a spooky Halloween prop.

Where Hoodoo comes from is not mystery or magic; it is history. Enslaved people from West and Central Africa brought their spiritual know-how with them into the Americas. That knowledge collided with the plants and medicines of Indigenous peoples, and later absorbed European folk remedies and books — and out of that improvisation Hoodoo emerged as a practical system for survival, healing, resistance, and spiritual care.

If you think Hoodoo is only a New Orleans thing, you’re partly right and partly wrong. New Orleans is famous for its visible Voodoo scene, and for good reason: the city’s Afro-Caribbean and West African roots helped produce a particular, public-facing set of rituals and personalities — think altars, gris-gris, and the long shadow of Marie Laveau. But Hoodoo proper is broader; it took root across the Gulf Coast, the Sea Islands, the Black Belt, and beyond. The coastal Lowcountry and the port cities are where African herbs, songs, and grief met the plants and pressures of the Americas and turned into everyday spiritual tech for Black people.

Mobile, Alabama, is part of that map. The story of Africatown and the Clotilda — the last known illegal slave ship to arrive in the United States — is not just tragic history, it is a living explanation for why African spiritual practices persisted there. The people who founded Africatown brought languages, medicines, and ritual knowledge with them; their descendants kept pieces of that culture alive whether or not white newspapers or history books paid attention. That continuity helps explain why rootwork and herbal healing were part of daily life in places that look, on a map, like the Deep South.

Let’s talk about what Hoodoo actually does, because the caricature of “devil worship” is lazy and convenient. Hoodoo is a toolbox: herbs, baths, poultices, charms, mojo bags, baths, petition papers, and yes, prayers and verses. It has always been about practical outcomes — protection from violence, healing the sick, pulling in wages, keeping a lover’s promise, or getting justice on somebody who’s been a problem.

In the Lowcountry, Gullah-Geechee herbal medicine was healthcare, because people could not depend on white doctors who ignored or harmed them. Today you’ll hear teachers and herbalists calling this ancestral medicine out loud again, because modern medicine still leaves gaps.

Now let’s handle the pew-side panic. Why did many Christian churches call Hoodoo evil? Two reasons, plain and messy: power, and ignorance.

Predominantly white Christian institutions in the U.S. built a narrative that anything African looked demonic as part of broader racist projects.

That stigma stuck, and over generations many Black preachers absorbed the language and used it to police behavior in their flocks.

But also, Hoodoo and Black Christianity were not always opposites. African-derived spiritualities and Black Christian worship interwove in countless ways — ring shouts, spirit possession, anointing oils, and praying Psalms in special tones. Some congregations hid conjure practices inside Christian language, and some rootworkers openly used the Bible as a tool. The point is this: calling Hoodoo “the devil” was often easier than sitting with how Black people kept spiritual power with whatever tools were at hand.

Yes, I said the Bible. Let that sink in for the people who were taught that Hoodoo and Christianity can’t possibly be friends. For many rootworkers the Bible is the original conjure book. Psalms, Proverbs, and specific verses show up in mojo bags, on petition papers, or chanted aloud during work because practitioners learned the spiritual grammar of scripture and turned it into a language for protection, reversal, and blessing. There’s even a whole history of “Secrets of the Psalms,” a grimoire that made its way into conjure practice and was adapted by Black practitioners. So if you were ever told Hoodoo is anti-Christian, tell someone gently that’s incorrect both historically and spiritually.

American folklorist and writer Zora Neale Hurston, c. 1935–43.

What about seers and rootworkers in the church — the folks who “shouldn’t” be there but were? They were not rare. Zora Neale Hurston and other folklorists documented Black congregations where prophecy, spiritual healing, and what outsiders called “conjuring” were part of worship. Sanctified churches and Spiritual churches blended ecstatic worship with practical conjure techniques. Women often carried the knowledge of herbs and the gift of sight; they were midwives, doctors, and spiritual counselors in communities that needed them. Maybe your great-grandma was a “mystic” by day and the church deacon’s neighbor by night, and both roles fed the same work: survival.

So how do we talk about Hoodoo to people who think “rootwork” equals “Satanic”? Start with facts and end with respect. The demonization of African-derived spiritualities is rooted in centuries of racism, exoticism, and fear. Hoodoo is not devil worship. It is a set of practices born from displacement, resilience, and the need to care for communities that white institutions often neglected. If you want to judge, judge the history of why people needed Hoodoo in the first place.

October is a good month for more than pumpkin patches. Hoodoo Heritage Month is an invitation — learn the roots, meet the practitioners, read the scholarship, and listen to the stories. If you walk away from this thinking it’s all spooky nonsense, at least do it with a little humility and a better vocabulary. These are people’s ancestors, healers, and survival strategies. That deserves more than a horror movie stereotype.

Follow Us On Social Media!